25 May 2016

Ramsay Burt

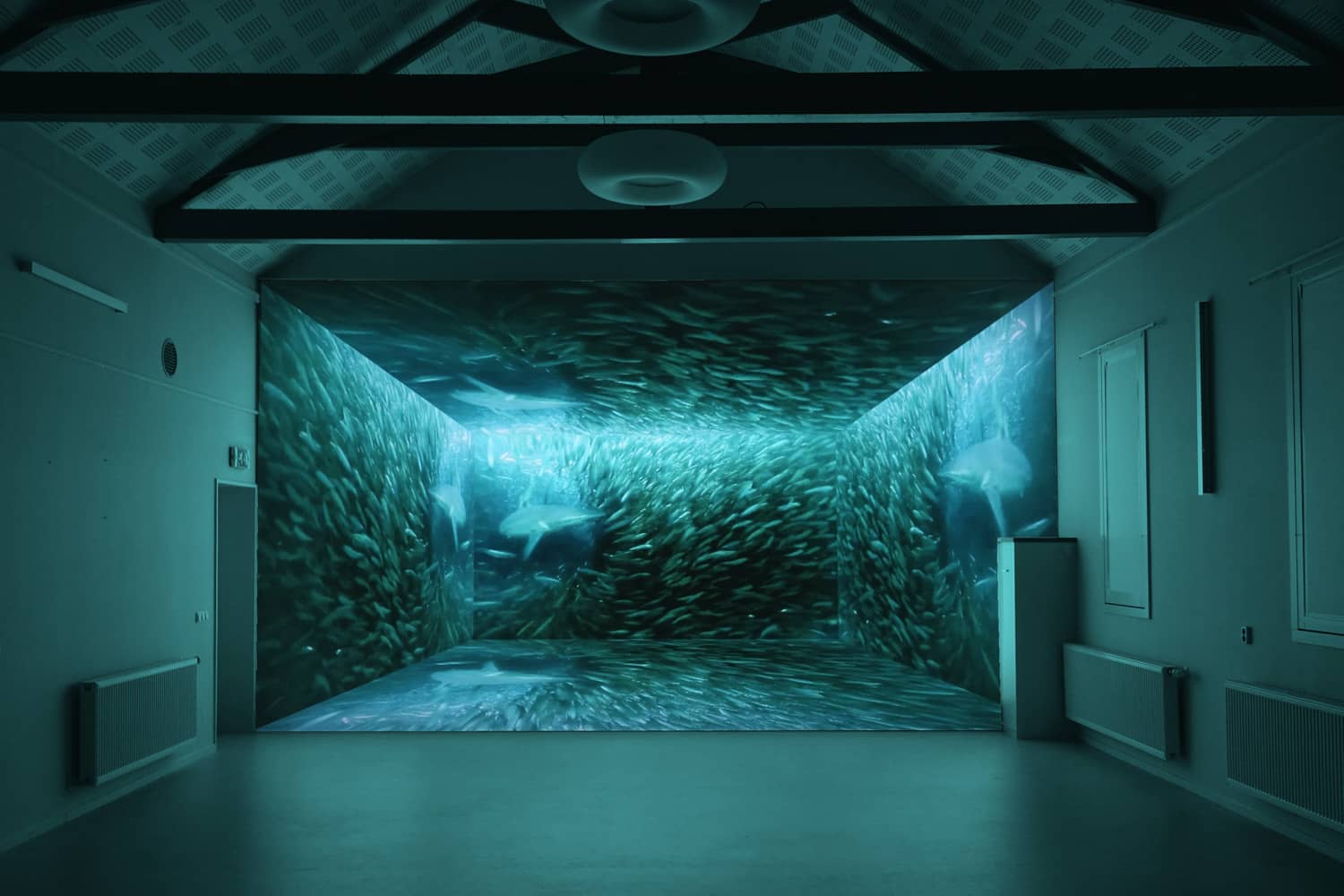

Walking into Andrea Božić and Julia Willms’ installation The Cube, before I’d even taken in its visual material, I was aware of being immersed in its loud, (but not painfully so) natural, atmospheric sound design. Then I focused on the projection on the end wall. This showed a semblance of a white cube-like space that extended or mirrored the walls and ceiling of the room in which I and my fellow spectators were sitting.

This part of the Stadsschouwburg has two mid-twentieth century modern chandeliers and two more virtual ones were hanging in line with them from the ceiling of the virtual cube. In the latter was a landscape which, after a few minutes, slowly merged into another one.

Many of the landscapes were Alpine. But there were also storms, a tornado, the Northern Lights, a shoal of little fishes swarming out of the way of predatory sharks, and a jellyfish that looked curiously as if it might be a distant relative of the Stadsschouwburg’s chandeliers. All these places and events always remained part of the white cube-like space, sometimes filling it, at other times contained in a box or as a low platform on the floor. Always at least some of the wall, or floor, or ceiling of the virtual extension of the room remained visible.

semblance and affordance

To a certain extent, The Cube was a semblance of a stage, and the projections were scenography, (Peter Pabst created some wonderful landscape-based sets with rocks and water for later Pina Bausch productions.) But, as I will discuss shortly, part of what is fascinating about The Cube is that you can’t really categorise it. What it does is afford its beholder an immersive experience.

The floor of the room in the Stadsschouwburg had large black tiles and their grid continued in the virtual space. The perspective wasn’t quite right from where I was sitting. It tipped up slightly like a raked stage. Very quickly I found that I’d forgotten this and was totally immersed in the projected landscapes.

J.J. Gibson worked, in the 1940s, for the US Air Force researching whether flight simulators were any use for the training of pilots. His conclusion was that the virtual spaces that they simulated were useful because they afforded trainee pilots opportunities for learning techniques that they could transfer to real situations. The Cube affords its beholders opportunities for imagination.

on top of the world

There are no real mountains in England, and nothing like the Alps in either Scotland or Wales. I love the Alps. I love the views you get from summits and high ridges; the little high valleys (Alpages) with wild flowers that don’t grow lower down; the little, very blue lakes nestling just below a summit or a high pass; the little pockets of rather grey snow one passes on high sheltered slopes still not melted in July; the high moonscapes of gravel where, if you look closely, you can find tiny little Alpine flowers like edelweiss, or the snail whose giant image slowly slides over gravel in one moment in The Cube.

romanticism?

It all sounds very romantic, like the sheer, sublime mountain scenes that artists like Turner and Caspar David Friedrich painted at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In these, the over-powering forces of nature made humans seem tiny and ineffectual. This is part of the cultural baggage that Božić and Willms are dealing with in The Cube.

It is obvious from what I’ve just written that I have an affective response to the imagery in The Cube. The particular landscapes they show – and not all of them are Alpine – avoid the sentimental clichés of the tourist brochure or the grandiose conventions of much C19th romantic landscape painting. The way we affect and are affected by the environment is as important now as it was in Turner’s day, perhaps even more important. There is a need for new ways of looking and thinking about human and non-human relations that are relevant to contemporary values and concerns.

gazing

Božić and Willms have written that:

In their [the beholder’s] encounter, the room acquires the properties of the organic and behaves as an organism itself. The viewer standing in the space becomes part of the organism, both through their implied physical presence in the work and the inner movement of the gaze and attention and the experience it evokes.

The way they have organised the different video sections and inserted them into the virtual space directed my gaze, made me see things through their eyes. Just as I did not have any difficulty accepting the slightly wonky perspective of the virtual cube-like space, neither did I have any problem following the radical cuts and changes of scale from one video scene to another.

One video section showed men on a stone-filled clearing surrounded by larches. This bit of landscape only occupied a small part of the back of the cube-like space and the men were miniature figures, wandering around in a slightly mysterious way – what were they doing exactly? what were they looking for? In another video section I could just begin to make out a group of tiny people on a misty, rocky prominence. Was that an orthodox Christian cross they were carrying, and why were they there? Contrasting with this Lilliputian world, was the giant snail, and the giant jellyfish.

Božić and Willms have developed a dramaturgy in The Cube that takes advantage of the habit of experiencing contemporaneity as a succession of random fragmented events. At the same time The Cube also offer me – with its slow, gradual succession of landscapes – an antidote to the disruptive speed of much contemporary media, of online or cable music videos for example, that aim to make their impact in the short duration of our distracted attention spans. The slow, immersive properties of The Cube slow me down and keep me watching.

human presence

A little, rectangular box on the virtual floor of the cube contains tiny holiday makers in a sunny landscape with very green grass – perhaps beside a lake. The people are ant-like but the sound of their chatting fills the installation as if I were there on holiday with them on this hot summer afternoon. Gradually the scene darkened and turned into another video of a storm over water which seemed to have been projected onto all the white walls and ceiling of the virtual room.

There are signs of human activity in other sections. A snowstorm blanked out the landscape and the sound of the wind deafened me with its white noise. It must have been filmed on a road somewhere because a triangular road sign was shaking and bending in the gale. This video faded into another looking down from high up in the mountains where there were still little patches of unmelted snow. A wandering line of pylons indicated that the viewpoint was above a ski lift, dismantled for the summer, and at the pylon’s bases was the unnaturally disturbed gravel track that in winter would again become a piste. This video section was interesting spatially but these signs of human activity robbed it of any potential for the romantic or picturesque. Božić and Willms were directing my gaze towards contemporary uses of natural spaces.

in-between

The Cube was made by a visual artist (Willms) in collaboration with a choreographer (Božić). The two of them have been collaborating on works for more than a decade. It was created for an exhibition that they curated Spectra: Light Like a Bird, Not Like a Feather at the Kunstraum am Schauplatz, in Vienna. I saw it as part of SPRING Performing Arts Festival, which mostly consisted of dance works. In a Fine Art context, The Cube is perhaps more theatrical than most installations in its stage-like organisation of virtual space. Seen in a dance festival one might ask: but where is the choreography?

The Cube is both dance and visual art and other things as well – like scenography, soundscape, and so on. It cannot be categorised or reduced to any one discipline. It exists in the spaces in between. Indeed trying to work out what it is, gets in the way of experiencing it for what it is, or of being open to what it affords.

Something that opens up a new way of thinking or offers a new kind of experience is political. We need new ways of telling stories because the old ways are so contaminated by habits of thinking and being that have got us into the situation we are in now, which is not a good one. Coming from somewhere that is in between and doesn’t quite fit with existing modes of categorisation is as good a starting point as any for trying to think and do things differently. The Cube affords beholders a wonderfully gentle, but deeply affecting way of doing precisely this.

Link: https://ramsayburt.wordpress.com/2016/05/25/andrea-bozic-and-julia-willms-the-cube-stadsschouwburg-utrecht-spring-festival/

Published on 25.05.2016